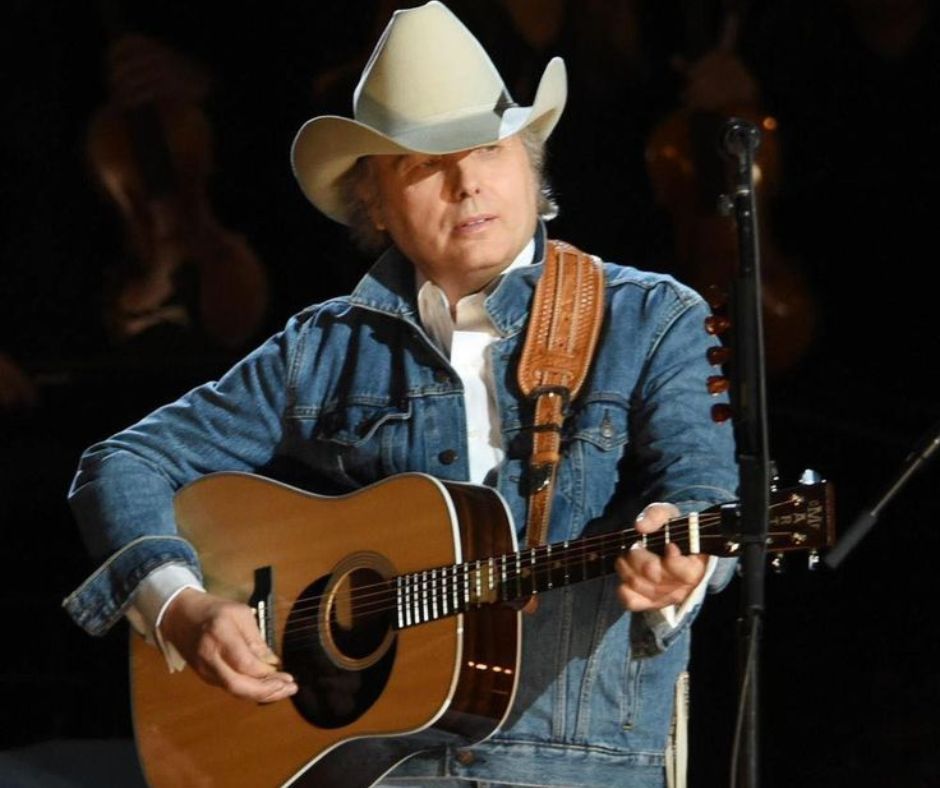

When Dwight Yoakam Revived the Elvis Song America Was Never Allowed to Hear

There are songs that become classics the moment they’re released. And then there are songs that almost disappeared—lost not because they failed, but because they were considered “too dangerous” for their time. “One Night,” the song Dwight Yoakam boldly revived in the 1990s, belongs to the second category. Most listeners don’t know that this emotional, pleading ballad was once a banned track from Elvis Presley’s early career.

The original version, titled “One Night of Sin,” was recorded by Elvis in 1957. But the problem was in the lyrics. They were deemed too provocative, too suggestive for the conservative era of the 1950s. Lines like “One night of sin is what I’m now paying for” made the record label nervous. They feared backlash from radio stations, religious groups, and national networks. So despite Elvis having already pushed the limits of American culture, “One Night of Sin” was shelved.

Elvis eventually re-recorded the song with softened lyrics—removing the word “sin,” reducing the sexual overtones, turning the track into something the public could digest. The newer, “clean” version was released and became a hit. But the original intent of the song—its raw desire, its emotional confession—was hidden from the world.

For decades, few people ever heard the real “One Night.”

Dwight Yoakam, growing up in Kentucky and later shaping his sound in Los Angeles honky-tonks, was among the musicians who felt the loss. Dwight was a lifelong Elvis admirer, but more than that, he was an artist obsessed with authenticity. His entire career was built on honoring the original spirit of American roots music: Buck Owens, Hank Williams, Elvis Presley, and the raw rockabilly fire that shaped them.

So when Dwight Yoakam decided to record “One Night” for the Honeymoon in Vegas soundtrack (1992), he didn’t want the softened version. He wanted the truth.

He wanted the version Elvis wasn’t allowed to release.

Dwight approached the song with a mixture of reverence and rebellion. He kept the longing, the ache, the vulnerable tone of a man begging for forgiveness—but restored the emotional intensity that had been muted in Elvis’s second version. His voice cracked with desperation in places, echoing the gritty textures of early rock & roll. The guitar lines were sharp, the rhythm section driving yet restrained, giving the song a tension that felt almost cinematic.

It wasn’t just a cover.

It was a reclamation.

Music critics pointed out immediately that Dwight was not simply paying tribute to Elvis—he was restoring a piece of musical history that had been silenced. In interviews, Dwight himself said he wanted to perform the track “as if Elvis was still in the room.” It was his way of honoring the man who shaped his sense of phrasing, swagger, and emotional delivery.

Listeners connected with Dwight’s version because it felt like the past had suddenly returned, alive and breathing again. The song wasn’t polished; it wasn’t modernized. It felt like a time capsule opened after 35 years, revealing a truth America had been denied.

Beyond nostalgia, “One Night” also highlighted something central to Dwight Yoakam’s career:

his refusal to let musical history be rewritten or sanitized.

At a time when Nashville production was becoming slick and formulaic, Dwight was willing to reach back into the gritty roots of American music and bring forward something honest—even controversial. His “One Night” may not be the version Elvis originally recorded word-for-word, but it carries the same spirit: the confession, the sin, the plea for redemption in the middle of a lonely night.

And perhaps that’s why the song still resonates today.

Because everyone has that one night—

the one mistake, the one heartbreak, the one memory that never quite leaves them.

Dwight Yoakam didn’t just revive a song.

He revived a feeling—

the dangerous, trembling, beautiful heart of rock & roll itself.